Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

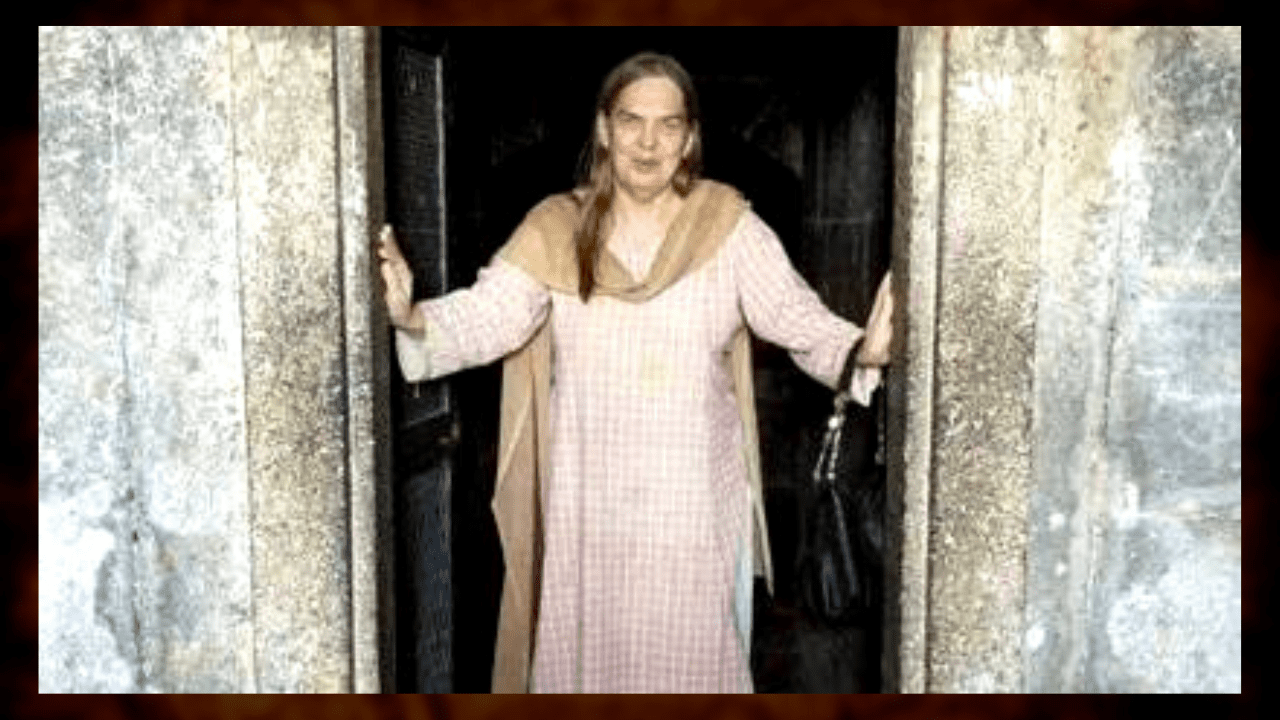

Gail omvedt

About Author

Gail omvedt was American by birth and Indian by heart. While living in India, he made a scathing attack on the disgraceful system of caste, which is a product of the Brahmin religion. In this work, he wrote many books on the social issues of Dalits and the emancipator of Bahujan Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. Here we are reviewing one of the best books by Dr Gail Omvedt, Seeking Begumpura: The Social Vision of Anti caste Intellectuals.

Introduction

In seeking Begumpura, the social vision of Anticaste Intellectuals, Gail Omvedt comprehensively describes, analyses, and puts forth for the readers an Indian version of utopia that is based on the vision of anticaste intellectuals as opposed to elite/Brahminical literature. She first puts forth the idea of ‘Kaliyuga,’ that is, a dystopic worldview of the future society, which is the point of view of the elite Hindu literature. She then contrasts this vision with the utopian vision in India, which arose from the lower levels of society. Such utopias were unavailable in Sanskrit and in Brahmanism, for whom the first yuga was the golden age, after which society falls into a cycle of depravity and degradation for the future to come. In contrast, anti-caste intellectuals offer the vision of an egalitarian, equalitarian future.

Book Review of Seeking Begumpura: The Social Vision of Anticaste Intellectuals

Gail Omvedt delves into the utopic and subaltern visions of various anti-caste intellectuals in detail, namely Namadeva, Kabir, Ravidas, Tukaram, Phule, Iyothee Thass, Ramabai, Periyar, and Ambedkar. Namdev stressed the power of the name, that is, repeating the name/s of God as sufficient. Reading the Vedas, shastras, performing rituals or renunciation was not needed. Further, an overarching characteristic of the radical bhaktas at the time was that they pursued their vision by remaining as ‘householders,’ thus showing an alternative path to devotion that is possible without renunciation. These Sants also went against the guru tradition by emphasising the need to ‘think for oneself.’ This has a parallel in the Buddhist dictum- ‘be your lamps, be your own refuge.’ Kabir’s utopia is of a place that is a non-place, a time that is beyond time. In his words: “The world died of reading tomes, no one turned out wise; from the single word of ‘love,’ wisdom will rise.” Ravidas propounded an earthly utopia in his poem ‘Begumpura,’ i.e., a sorrowless city with a sorrowless name, with no pain and no taxes, no wrong, where no one owns the property, and all are one, living as friends. Tukaram similarly envisioned Pandharpur as a utopia where time and death cannot reach, and it is a place full of love, without hierarchies. Dr Gail Omvedt then describes in detail how these ideas of bhakti were later brahmanized to exclude the lower sections of society from whom these ideas emanated in the first place, and in a sense, turning these ideas of utopia upside down and making them dystopic.

Phule drew inspiration for his utopia, that is, the Satyashodhak Samaj, from another utopia, that is, the kingdom of Baliraja. He thus propounded an alternative, monotheistic, universal religion of compassion. A nation for him was to be built on the development of the individual with the feeling of commonness. Iyothee Thass envisioned a Buddhist utopia as it was in the past, where Dalits were originally Buddhists. He thus construed conversion in present times as reversion, i.e., a return home. Ramabai sought to establish a utopia in practice by reintegrating widows into society in a way male reformers couldn’t think of as the latter’s solution was ideally remarriage, that is, reintegrating women into the existing patriarchal structures.

Periyar in modern times had a more concrete utopian vision. For instance, in his idea of Dravidanadu, he perceived the relation between economics and religion and saw technology as a crucial human advantage that would help the lower castes overcome their drudgery of labour and provide leisure. Finally, Ambedkar’s utopia is one of ‘Prabuddha Bharat’, which is reflected in his modern ideas, which were pragmatic in economic and social terms. His priority was to ensure that such systems be created where social and economic exploitation of the lower castes would be minimised and poverty would be eradicated. In choosing Buddhism, he sought to unite his utopia of economics, politics, and religious-cultural vision to ensure freedom from slavery of all kinds.

In all these utopic visions, the individual is kept at the centre through which a common good is to be derived and established, establishing an egalitarian utopia in turn. Today, there is a need to be educated, agitated, and organised so that work on establishing these utopias may be reclaimed and sustained on a large scale to avoid further co-optation, brahminization, casteization and dystopianization of the utopic vision of anti-caste intellectuals.

Book quality & availability

This book was published by Navyana Publication House on 01 January 2009. It is available only in the English language. If you want to read Seeking Begumpura: The Social Vision of Anticaste Intellectuals, you can buy it on Amazon.

This review was written by Dr Ashan Singh